Water Chestnut Invasion

June 26, 2024

Published June 6, 2024

What is water chestnut?

Water chestnut, also known as European water chestnut (Trapa natans), is an aquatic plant native to Europe, Asia, and Africa (not to be confused with water chestnuts found in Asian cuisine!). Here in Massachusetts and the rest of the Northeast, they are an invasive species that alter and harm freshwater environments. The plant appears as floating, diamond-shaped leaves connected to the stem by a long, flexible submerged stalk, with sharp nuts at the bottom of the root.

This aquatic invasive is an annual plant, which means it completes its entire life cycle from seed to seed, in just one growing season: it grows, blooms, makes seeds, and dies, all within one year. The plant emerges in early May and grows throughout June and July. It continues to flower until early Fall or when the first frost begins. Water chestnut thrives in slow-moving, nutrient-rich, fresh water with muddy bottoms. Unfortunately, our waterways, the Concord, Sudbury, and Assabet rivers, fit this description. The rivers’ slowest moving sections are mainly where dam impoundments are located, where water tends to be richer in nutrients, or, in other words, where you’ll most likely find the largest concentrations of water chestnut. The plant spreads via its seeds, which can lay dormant in the sediment for more than 12 years! Each seed can produce 10 to 15 stems with submerged and floating leaves, terminating in a floating rosette. Each rosette is capable of producing up to 20 seeds.

History of water chestnuts

While accounts vary, most agree that Trapa natans was introduced to North America in Middlesex County, Massachusetts, in the 1870s. By 1874, the plant was cultivated for its water-lily-like appearance in the Asa Gray Botanical Garden at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Water chestnut was first observed in North America near Concord, Massachusetts in 1859 and in the Charles River in 1877 but quickly spread throughout the Northeast, mainly Massachusetts, Vermont, Connecticut, New York, Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Virginia.

Why is water chestnut a problem?

You may often hear that invasive species are a danger to ecosystems. It’s in the name: an invasion is never a good thing. But what does this actually mean? And how does water chestnut specifically harm our local freshwater ecosystems? Because water chestnut is not a native species, there are little to no native organisms that eat them to regulate their growth.

Consequently, they can grow rapidly and form dense mats on the water surface, outcompeting native plants for light, nutrients, and space. This can lead to a loss of native plants and a consequent decrease in biodiversity, which disrupts the balance of the ecosystem. The dense mats formed by water chestnut impede the movement of native fish, block sunlight from reaching submerged plants, and reduce oxygen levels in the water.

Water chestnut can also negatively influence nutrient cycling in freshwater ecosystems. Because they are annual plants, they grow and decompose quickly, causing a fluctuation in nutrient levels, which can contribute to algal blooms, further disrupting ecosystem balances. As they grow and form dense mats on the water’s surface, the plants can collect and hold organic matter such as leaves, twigs, and other debris. When trapped within the thick beds of water chestnut, these materials undergo decomposition. When the organic waste breaks down, it releases nutrients such as nitrogen and phosphorus into the water. While these nutrients are essential for plant growth, excessive amounts can lead to eutrophication, a process where nutrient levels that are too high cause an overgrowth of algae and other aquatic plants, which further depletes oxygen levels in the water depriving fish and aquatic organisms of oxygen and harming the ecosystem balance. Trapped organic waste can additionally provide an environment for bacterial growth in water, which also consumes oxygen during decomposition, creating conditions unsuitable for native populations.

The dense growth of water chestnut can also impact recreational activities such as fishing and swimming, and it can significantly hinder boat movement by clogging waterways.

YOU can help!

You can help prevent water chestnut from covering and clogging our rivers! How? By removing the plants by hand or tracking them when you come across them so others can.

HERE’S HOW.

First, familiarize yourself with what water chestnut looks like:

- Floating leaves form a rosette

- The diamond-shaped leaves are toothed on two sides and connect to the stem by a long, flexible, submerged stalk.

- Submerged leaves are featherlike, whorled around a stem

- Sharp four-pointed nuts may be attached at the bottom of the root, and new nuts will be formed under the rosette.

Once you can identify water chestnut, start removing or tracking them!

REMOVING

Hand-pulling infested areas repeatedly is the most effective way to achieve long-term control.

- The best time to pull is when the plants first appear at the water surface in early May. They are young and small, and you should gently pull up the whole plant, including its roots.

- As the rosettes get larger (up to 15”), grip the stem firmly and pull, breaking it off below the submerged leaves just above the roots. This will prevent them from re-sprouting and keep mud out of your boat.

- By August, the nuts are maturing, so carefully flip over the rosette and break it off to prevent the nuts from dropping off. You can avoid dropping mature seeds and disturbing the sediment by only pulling the rosette and not taking the entire plant.

- Place what you pull into your boat (we take a laundry basket or other container with holes to fill with them as we pull, draining out the water and keeping rosettes and nuts from escaping and starting new infestations).

DISPOSAL

Any disposal method used must ensure that there is no possibility for viable plants or seeds to be re-released into the river.

- Bag and take home for disposal or composting. Composting is the best, but the plants must be away from the water and above the floodplain.

- Remember: you are not finished until you clean your boat carefully to avoid carrying invasive plants to other water bodies.

No Aquatic Hitchhikers! Clean, Drain, and Dry all equipment!

TRACKING

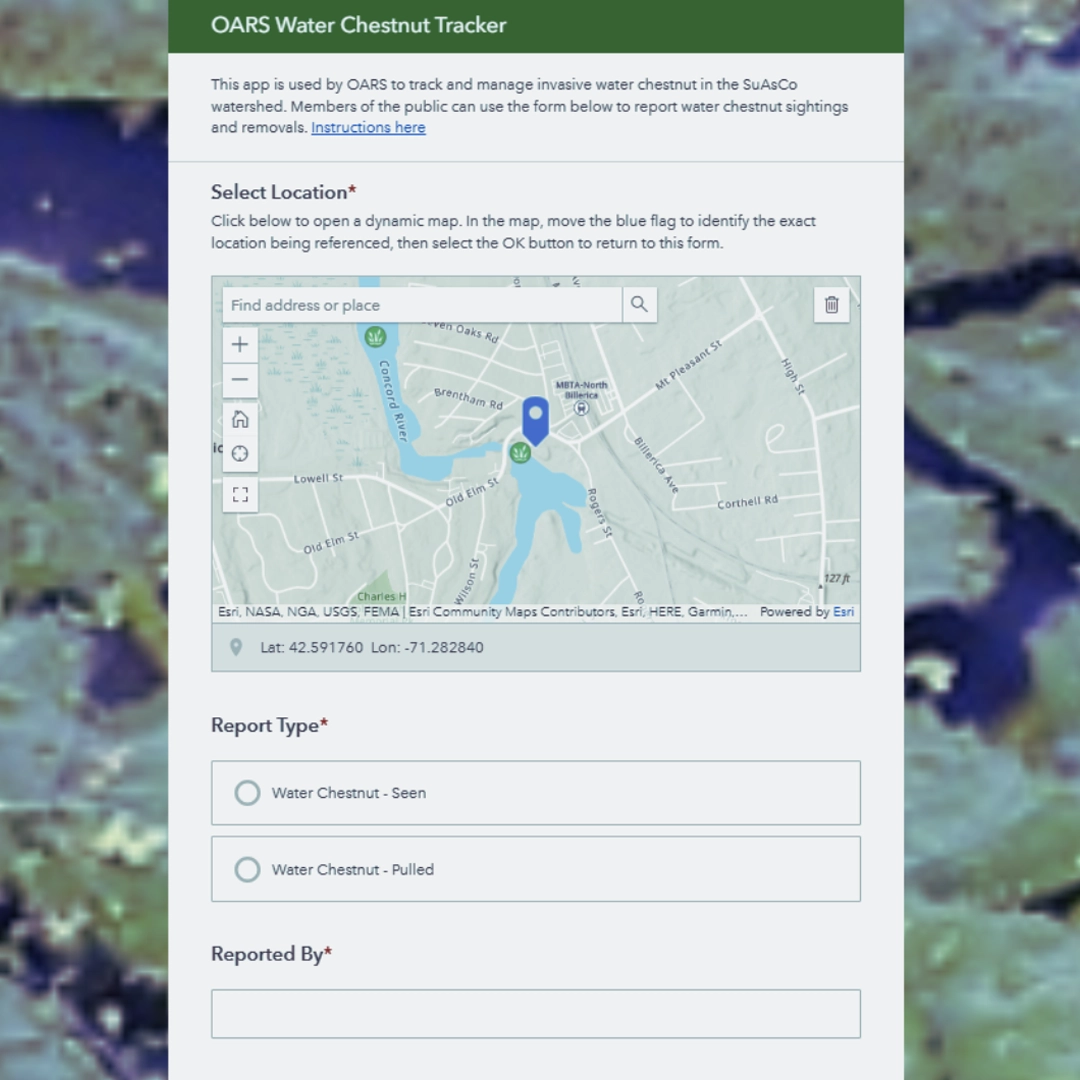

Use our reporting app to share with us and other river users where you have seen or pulled water chestnut.

Reporting App Instructions:

Reporting App Instructions:

- Zoom in on the map to the location where you have seen or pulled water chestnut and click once to drop a pin

- Select Report Type: “Water Chestnut—seen” or “Water Chestnut—Pulled”

- Enter your name and email so we can follow up with you if needed

- Estimate the number of rosettes you saw or that were left after your pull

- Enter the number of Bushels (Baskets) you collected

- Attach a photo if possible

Complete these steps either on-site near the river or once you return home

Zoe Green is a Junior at Skidmore College double majoring in Environmental Studies and English. She is currently volunteering her time with OARS to do blog pieces and paddling the rivers to report water chestnut on the rivers.